Without a consistent approach to sex-and-age-disaggregated-data (SADD) in local, national and international data collection, the specific needs of women and girls – as well as men and boys – will continue to be misunderstood or overlooked by international development agents and disaster relief operators. The same is true for understanding the needs of the LGBT community in a disaster.

Image by Mohamed Hassan from Pixabay

Women and children, and in some cases men and boys, should not be more likely to die or be injured in a natural disaster. Yet a brief review of the literature on the disproportionate effects disasters place on different genders reveals that boys, girls, men and women can all be overlooked in humanitarian response for different reasons.

Previous studies have shown that key challenges in health, provision of shelter, food security and women’s safety – to mention but a few examples – cannot be solved with a one-profile-fits-all approach to data collection and analysis. Otherwise certain groups remain marginalised and the support they need does not reach them.

Needs differ, even in a disaster

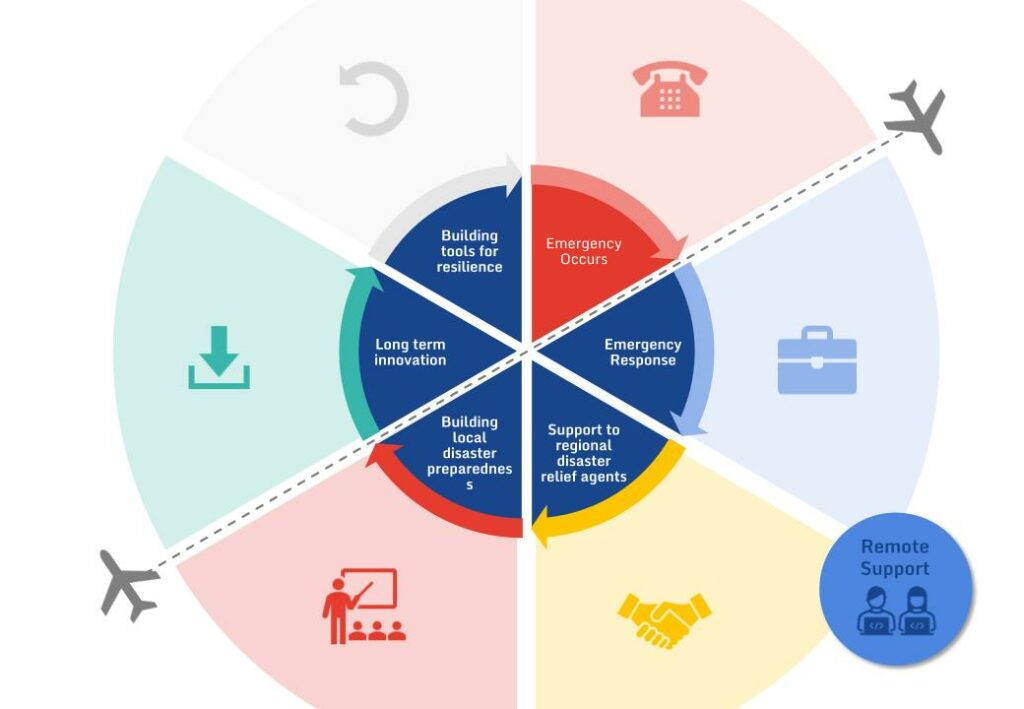

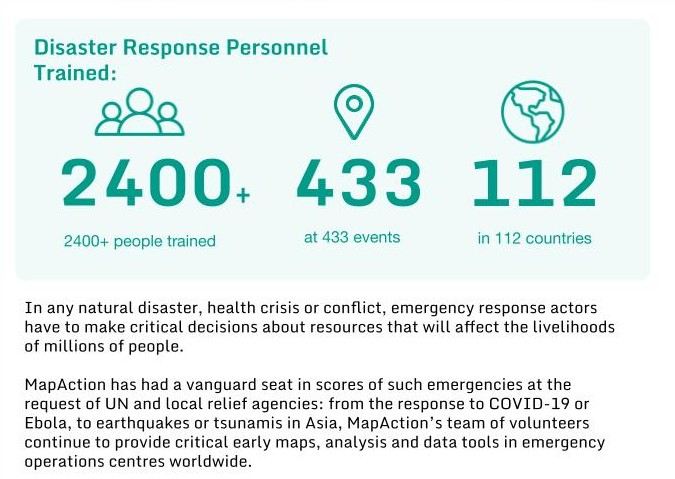

MapAction, a humanitarian mapping charity that maps disaster landscapes, needs the right data to make the right maps to support decision-makers. Decisions based on SADD can be critical, yet hard to source. To get a better understanding of the need for more SADD in humanitarian response, MapAction interviewed representatives from 10 stakeholder organisations and reviewed dozens of specialist academic reviews on SADD in humanitarian data collection and response.

The process revealed that sometimes something as simple as stigma can be the key factor in misunderstanding gender-specific needs in a disaster. During the cholera outbreak in Haiti in 2011, for example, SADD revealed that more men were dying and fewer men were attending clinics than women. This led to the discovery that men needed more education on the symptoms and highlighted where men had been hiding their symptoms because they confused them with HIV, which had associated stigma, notes a case study in the EU’s Gender-Age Toolkit.

Another report by UN Women also found that people who identify as LGBT suffer more before and after a disaster. “The authors found that the discrimination, violence and isolation LGBT people face before, during and after emergencies weakens their ability to live resilient and dignified lives, survive and recover. And humanitarian and disaster response organizations do not appear to be systematically dealing with the problem, they say,” states UN Women in a summary of the report The Only Way Up that looked at cases in Myanmar, the Philippines and Vanuatu.

An interesting case study from Eritrea showed that adolescent demobilised male fighters were experiencing severe malnutrition because they did not know how to cook and had nobody to cook for them. While cases such as these highlight male margination, it is women and girls who continue to experience the most disproportionate impact because of unresolved gender parity issues, especially in societies with stronger patriarchal attitudes. “Gender equality is growing more distant. UN Women puts it 300 years away,” António Guterres, secretary general of the UN, told the UN Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) in March 2023.

Women most affected

In Pakistan, for example, a 2009 review of World Food Programme (WFP) food ration recipients identified 95% of registered men were collecting rations, but only 55% of women. This triggered further investigation that led to understanding the access constraints affecting women, states a multi-stakeholder report from 2011.

Another example showed that female victims of natural disasters in Pakistan refused to be transported by male helicopter pilots because of potential stigma and fear of repercussions from male relatives. Stakeholders from major INGOs interviewed by MapAction for this study also cited striking other examples of gender imbalance in aid provision from Tanzania, Somalia and Sri Lanka. Understanding the role gender plays in each territory and context is vital.

Globally natural disasters kill more women than men and often at a younger age, observed a World Health Organization (WHO) study. Gender and age both matter in terms of who dies, who is injured and whose lives are impacted in what ways during and after the crisis, note Mazurana and Proctor in the The Routledge Companion to Humanitarian Action.

Data challenge

That is why sex-and-age-disaggregated data (SADD) is key. SADD highlights how people are affected differently depending on their age and gender, notes a 2021 report by the office of the United Nations Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). Disaggregated data is key for example when modelling differences in development, mortality and disease risk, allowing for more targeting of specific at risk groups, states an earlier study on gender, data and international crisis response. Disaggregated data is also vital for understanding vulnerabilities, needs and barriers to access during a humanitarian response.

Culture and politics play a role

Yet often SADD is sadly not available. “It is commonly argued that ‘paying attention to gender issues may not be timely or practical on the ground,’ i.e. the so-called ‘tyranny of the urgent,’” notes a study by the Swedish development agency Sida, while emphasising the role that SADD can play for “effective relief and lifesaving assistance.”

Beyond the will to collect such data, there are logistical and technical challenges. SADD can be complex to interpret and better formatting and presentation are needed to improve adoption for programming decisions. Others have noted that where SADD is collected, there are reports of inconsistent collection, inconsistent data management and inconsistent analysis and use. There are also challenges associated with data sharing, with a lack of coordination and data quality concerns. Data collected locally are also sometimes not shared or aggregated at a national level in a way that loses the SADD which was collected.

More SADD, please!

We believe the brief and non-exhaustive list of recommendations and resources below will help strengthen our own and our partners’ role in pushing for the availability and mainstreaming of more SADD for humanitarian response.

- The more people who are asking how gender is being considered during assessments, or requesting SADD, the more likely it is to begin to be more systematically considered. This should include sharing of knowledge and best practices with partners and in the humanitarian ecosystem;

- Identify community groups and agencies that may be key to helping inform and include a gender perspective;

- Training and awareness raising. It is not just after a disaster occurs that SADD matters, it is also important in anticipatory action. Integrating protection, gender and inclusion considerations into anticipatory action interventions is a crucial step in tackling the intersecting vulnerabilities that affect the delivery of humanitarian assistance. It also helps to ensure that any assistance provided does not exacerbate these vulnerabilities.

USEFUL RESOURCES

The Gender Handbook for Humanitarian Action, Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IACS)

Gender in Emergencies, Care Emergency Toolkit

Oxfam Minimum Standards for Gender in Emergencies, Oxfam

A Little Gender Handbook for Emergencies, Oxfam

READ ALSO: CoP 27 : Good use of data is key to mitigating the climate emergency